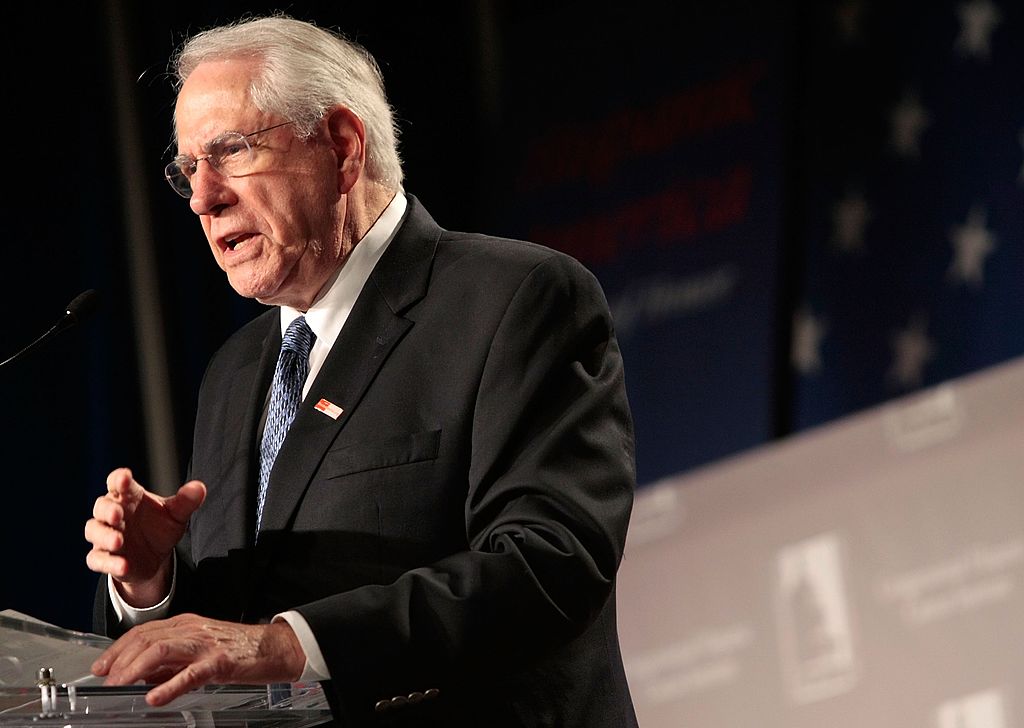

What I learned from Mike Gravel are lessons ignored, even mocked by the establishment, writes Joe Lauria.

I first met Sen. Mike Gravel in the lobby of the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York in early 2006 after a mutual friend told me Gravel was contemplating running for president.

Our Waldorf breakfast lasted four hours. I was surprised that such an American politician existed. He seemed to lack the expected self-importance. More incredibly, I agreed with him on every point of public policy–foreign and domestic. Having been a reporter for decades–I was a correspondent for The Boston Globe at the time–I’d surpassed the average citizen’s cynicism about people in government.

But here was a former United States senator questioning the most fundamental and seemingly unshakeable myths that underpin a brutal status-quo. The central myth, affecting foreign and domestic policy, is that U.S. behavior abroad is driven by an altruistic need to spread democracy and that its vast military machine is defensive in nature. If Americans would be convinced that the opposite is true, the edifice of lies that supports an imperial house of cards could crumble.

Here was someone from the heart of the system vowing to undermine it by declaring–eventually on a debate stage with Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama and Joe Biden–that Americans’ motives abroad are avaricious and aggressive, its military offensive, and its consequence death and destruction, not democracy.

It is suicidal for a politician to tell American voters that America’s motives are impure, that they are not the “good guys” in the world, and that money that should be spent on them at home is wasted destroying innocent lives abroad.

But that is what Gravel was prepared to do. He told me of his plan to run for president. He knew he had no chance, but was convinced by others to use the run to promote direct democracy and to tear down the deceptions.

I agreed to cover his campaign to highlight the crucial issues that he was raising that the mainstream would denigrate or ignore. I was at the National Press Club in Washington when he declared in April 2006, a full two and a half years before the election, and broke the story for the Drudge Report. In his announcement speech Gravel made his pitch for direct democracy. He said:

“Our country needs a renewal–renewal not just of particular policies, or of particular people, but of democracy itself…. Representative government is mired in a culture of lies and corruption. The corrupting influence of money has created a class of professional politicians raising huge sums to maintain their power. These politicians then legislate later in the interests of the corporations and interest groups that put up the money.

Are today’s politicians any more corrupt than those of earlier days? I don’t think so. Most men and women enter public service and begin with an attitude and a concern for the public good. It’s the power they hold that corrupts them. Throwing the rascals out–Democrats or Republicans, or for that matter any party may make us feel a little better, may give us some therapy, but reshuffling the deck won’t make any difference….

Equipping Americans with deliberative lawmaking tools will unleash civic creativity beyond imagination. A partnership of citizen-lawmakers makers with their elected legislators will in fact make representative government … more responsive to the needs of people.”

When an AP reporter asked him what was to stop the people from bankrupting the nation in their self-interest, Gravel told him that in the 100-year record of state initiatives that had never happened and the reason why was because it was the people’s money. Mike firmly believed that if Americans could vote on national policy the troops at the time would come home from Iraq and they’d only vote to send their sons and daughters to die if the U.S. were attacked at home.

I next saw Gravel at a dinner in June that year commemorating the 35th anniversary of his reading of the Pentagon Papers in Congress. The dinner was held at the Mayflower Hotel in Washington, where Gravel in June 1971 got a copy of the Papers indirectly from whistleblower Dan Ellsberg, who was at the dinner, disagreeing on minor details of how it all happened.

I soon found myself on the campaign trail with Mike, trudging up the steps of the state capitol in Des Moines, driving through a blizzard at Lake Tahoe after covering the first joint event with the other Democratic candidates and then sitting right behind Michelle Obama and to the right of Sen. Christopher Dodd’s sister at the first Democratic presidential debate in Orangeburg, South Carolina on April 26, 2007.

Gravel was probably the most talked about candidate after that debate for the things he dared say, such as the war in Iraq “was lost the day George Bush invaded on a fraudulent basis.”

Gravel said some of the other candidates “frightened” him. “When you have mainline candidates who turn around and say there’s nothing off the table with respect to Iran, that’s code for using nukes. If I’m president of the United States there will be no pre-emptive wars with nuclear devices. It’s immoral and it’s been immoral for the past 50 years as part of American foreign policy.”

The other candidates laughed and mocked him. “I’m not planning on nuking anybody Mike,” Obama said. On a talk show later, when Obama was asked how tough campaigning is, he said it was very tough when you had to get up on a cold Iowa morning and had to listen to Mike Gravel.

When the debate moderator Brian Williams asked Gravel who exactly frightened him, Mike said:

“The top tier ones. Oh Joe [Biden] I’ll include you too. You have a certain arrogance too. You want to tell the Iraqis how to run their country. I gotta tell you we should just plain get out. It’s their country. They are asking us to leave and we insist on staying there.

You hear that the soldiers will have died in vain. The entire deaths of Vietnam died in vain and they are dying this very second. Do you know what’s worse than a soldier dying in vain? More soldiers dying in vain. That’s what’s worse.”

Later Williams asked him, “Other than Iraq, list the other important enemies to the United States.”

“We don’t have any important enemies,” Gravel said.

“What we need to do is deal with the rest of the world as equals. We don’t do that. We spend more as a nation on defense than all the rest of the world put together. Who are we afraid of? Who are you afraid of Brian? I’m not.

“Iraq has never been a threat to us. We invaded them. I mean it’s unbelievable. The military-industrial-complex not only controls our government lock, stock and barrel,” and here he looked over at the other candidates all in government at the time, “but they control our culture.”

That crystallized it for me. Like every other American I grew up under the sway of heavy propaganda that portrayed the U.S. as a victim of other nations’ aggression, rather than being the perpetrator of it. It was one of many, many things I learned from Mike Gravel, and that others would benefit learning too.

When the debate was over I joined Mike on the stage. All the candidates and their wives were glad-handing each other. Mike said he had no time for that so we retreated to the green room. On the way I told him I hadn’t figured out Obama yet. But Mike told me, “He’s a fraud.” It turned out he was right about that too.

Growing Up

At some point during the campaign we decided to do a book together. I spent hours interviewing Mike and researching his history in the Senate. I traveled to Alaska and met his allies and enemies. I went to Philadelphia to see his sister. We then traveled together by car to Quebec to see the town where his father came from and visit his relatives there.

On the way up we stopped in New Haven, Connecticut to get something to eat. A bunch of Yale students recognized him and crowded around the table. Though we were running late he spent about two hours charming them.

In doing the book I learned about Mike growing up in Depression-era Springfield, Massachusetts, working in his father’s paint business, which gave him an appreciation of laborers, and his faith that ordinary people can run the nations’ affairs.

It was during Gravel’s time as an Army counter-intelligence officer in Germany during the 1950s that his life-long distrust of intelligence agencies was spawned. His job was to listen in to other people’s conversations, a job that he reviled. As he spoke only French at home as a child, he was sent to France to infiltrate communist rallies where he went undetected as long as his Quebecois accent wasn’t discovered.

When he returned home from Europe Gravel drove a cab in New York while he studied economics at Columbia. He kept a crowbar under his seat and once chased a would-be robber with it in a Manhattan intersection.

Having decided on a career in politics, Gravel staked out for Alaska, then still a territory, where he thought he had a shot. He arrived in Alaska on August 26, 1956 the day I was born. He first worked on a railroad clearing moose from the tracks.

When he was elected to the state house of representatives he took an interest in indigenous communities in remote areas and was instrumental in setting up high schools for them and when in the U.S. Senate helped settle their long-running land claims.

Even before he was sworn into the Senate he showed he was his own man, standing up to Ted Kennedy who wanted to make him part of the Kennedy clique. It was in the Senate during the Cold War that Gravel made his mark as an anti-militarist. After traveling to a war zone in Vietnam he sponsored legislation to defund the war, then to normalize relations with China before Henry Kissinger’s secret trip to Beijing set up Richard Nixon’s opening and Gravel topped it off with being the only senator to take the Pentagon Papers from Ellsberg and read them into the record in a bid to end the war.

A Political Odyssey

I also learned that Mike was a crafty politician. In the book he admits to lying on several occasions, including that he supported the Vietnam War, when he really opposed it, in order to get elected to the Senate.

That craftiness was put to good use as Mike fought several battles with the publisher on my behalf. But he did not like my title and the publisher chewed me out for daring to suggest the cover to the right that was rejected.

While I was in Alaska Mike barked at me over the phone that the title would be A Political Odyssey. I added the subtitle: The Rise of American Militarism and One Man’s Fight to Stop It.

In the week that Mike died Consortium News has coincidentally been publishing excerpts from the book about Gravel’s reading of the Pentagon Papers in Congress, which happened 50 years ago to the day this Tuesday.

I was told by people close to me that I was getting too close to the subject I was writing about, complicated by the fact the book was in Gravel’s voice and would have his name on it.

After the book came out, when we were interviewed by Leonard Lopate on his WNYC radio show, Lopate directly asked me on air how I could be an objective journalist in a book like this.

My response was that I challenged Gravel on many things he told me and fact-checked the major parts of his story in addition to doing copious amounts of original research. The truth was I agreed with Gravel on nearly every policy and was in no conflict writing about it, unlike in my work for major corporate media.

To the End

Gravel remained active on issues he cared about until the end. Just days before he died he was complaining about the evils of U.S. intelligence agencies. He was ridiculed when a few years ago he said at a conference that the government had suppressed information about UFOs. Last week the Pentagon released a report about hundreds of UFO sightings.

Gravel played a critical role in releasing the classified 28-page chapter from the 2002 Joint Congressional Commission study of 9/11 that highlighted Saudi officials’ involvement. He met with sitting senators and congressman in 2016 to press them that they had the right to release any information they wanted based on the Speech and Debate clause of the constitution and the precedent Gravel set in releasing the Pentagon Papers and having the Supreme Court confirm that right.

Representative Steven Lynch, one of the leaders of the fight along with the late Rep. Walter Jones, raised the Gravel precedent at a Capitol Hill press conference, essentially telling reporters that the group of Representatives could “pull a Gravel” and make the content known to the public without fear of prosecution. That helped move Obama to release the critical pages.

I stayed in touch with Mike in the years since the campaign and he was always supportive. I wrote the foreword to his last book, The Failure of Representative Government and the Solution: A Legislature of the People. When I became editor of this site Mike agreed to join the board of directors. He also became a huge supporter of Julian Assange and of the work we have done covering his extradition ordeal.

Mike’s Pentagon Papers case, in which Gravel sued Nixon and it reached the Supreme Court, dealt with identical issues. Gravel, his aide and Beacon Press, which published the Senator Gravel Edition of the Papers, all faced prosecution under the Espionage Act for publishing government secrets. Unlike Assange, Gravel escaped indictment.

At the time of the Pentagon Papers episode The New York Times ripped Gravel in an article entitled “Impetuous Senator.” A photo of Gravel appeared reading the Papers, with the caption, “A bundle of contradictions.”

The story, by Warren Weaver Jr., began: “The latest indoor sport on Capitol Hill is to try to guess what impelled Maurice Robert Gravel, a forty-one-year old Alaskan real estate developer, to attempt to read a part of the Pentagon papers into the public record, and ultimately to burst into uncontrollable tears.”

The Times then ridiculously went on to speculate that because he was born on May 13, 1930, under Taurus, the sign of the bull, that Gravel was “inclined to extremes and to impulsive actions.” He was contradictory, the Times said, because Gravel voted “with the liberals but against their leadership candidates and against their efforts to curb the filibuster. He loves the Senate but offends its elders. He is highly image-conscious but behaves in ways that mar his own reputation.”

The Times obituary Sunday on Gravel picked up where the newspaper left off exactly 50 years ago. It said he was “perhaps better known as an unabashed attention-getter, in one case reading the Pentagon Papers aloud at a hearing at a time when newspapers were barred from publishing.” It denigrated Mike’s courageous reading of the Papers as “grandstanding.”

To the end the establishment hated Mike Gravel. And Mike welcomed their hatred. He told the American people what they did not want them to hear.

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, Sunday Times of London and numerous other newspapers. He began his professional career as a stringer for The New York Times. He can be reached at joelauria@consortiumnews.com and followed on Twitter @unjoe .

SOURCE: https://consortiumnews.com/2021/06/27/what-mike-gravel-meant/